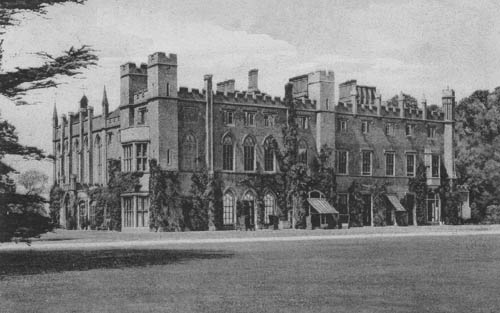

Cassiobury House

Hertfordshire

| Location | Watford | ||

| Year demolished | 1927 | ||

| Reason | Insufficient wealth and urban growth | ||

| See all images: | Gallery | ||

| << Back to the main list |

Cassiobury was perhaps not the most architecturally beautiful house but it was an important example of a long-held family seat, close to London, worked on by some of the most famous architects and craftsmen, and with a superb collection of art. However, the financial and urban pressures of the early 20th-century were to prove too great.

The Capel family owned the estate from the early 16th-century until the 20th. Arthur Capel inherited the estate via his wife, Elizabeth, the only surviving child of Sir Charles Morison, in 1628. However the Capels were already established at their Suffolk estate, Hadham Hall and so didn't move to Cassiobury. At the start of the Civil War Arthur was a Parliamentarian but he became disaffected by their violent methods and switched to the King's side. Unfortunately for Arthur Capel, or Baron Capel since 1641, his military career for the King ended with his defeat in the siege at Colchester, after which he was captured, held in the Tower of London, and then beheaded in 1649.

The Capel family owned the estate from the early 16th-century until the 20th. Arthur Capel inherited the estate via his wife, Elizabeth, the only surviving child of Sir Charles Morison, in 1628. However the Capels were already established at their Suffolk estate, Hadham Hall and so didn't move to Cassiobury. At the start of the Civil War Arthur was a Parliamentarian but he became disaffected by their violent methods and switched to the King's side. Unfortunately for Arthur Capel, or Baron Capel since 1641, his military career for the King ended with his defeat in the siege at Colchester, after which he was captured, held in the Tower of London, and then beheaded in 1649.

With Arthur's death, the Cassiobury estate was sequestered and Elizabeth Capel lived at Hadham until the Restoration of Charles II in 1660. The estates were restored to the family and Arthur, the eldest son and heir was awarded the titles, Viscount Malden and Earl of Essex. In 1668 Arthur moved the family from Hadham Hall to Cassiobury whilst he developed his political career which included a spell as Ambassador to Denmark. After a later quarrel he retired to his much-altered Cassiobury.

Relatively little is actually known about the original house which had been built by Sir Richard Morison soon after he had been granted the lands by Henry VIII in the late 1540s. It was described as;

"...a fair and large house, situated upon a dry hill, not far from a pleasant river in a fair park..."

However, no images of this house exist but the original form of the house can be seen in later engravings showing Hugh May's later additions. The North-West wing is in a markedly different Tudor or Elizabethan style with bay windows, gables and high chimneys. An inventory of 1599 describes a house of fifty-six rooms and outbuildings which gives a good indication of the size and status of the house. The Capels interest in art can already be seen in that the same inventory pictures are listed in eight rooms, totalling thirty-four in all. Although this sounds small, by comparison, even the richest collectors such as Elizabeth I's favourite, Lord Leicester, or the immensely wealthy Earl of Suffolk, had collections of only around 200 pictures, usually split between their London and country residences.

Whilst Arthur Capel was pursuing his political career abroad he had engaged the well-known architect Hugh May (b.1621 - d.1684) - described in Samuel Pepys' Diary as 'a very ingenious man' - to create a new house, incorporating the old between c1674-80. The layout of Cassiobury owed less to internal convenience and more to external show which resulted in a more spread-out plan in contrast to May's other work at Eltham Lodge or Moor Park which were 'triple-' and 'double-pile' respectively. Work was slow with May regularly requesting money from Capel, who was then in Ireland in his role as Lord Lieutenant.

May kept the one wing of the Morison house but added a central wing with pediment to which he then added a second wing to create an 'H'. Retaining part of the old house was regarded as a mistake, even by contemporaries, as it created an awkward plan which was never really resolved. This Cassiobury was an elegant Palladian design, though it might be argued a little plain with the only relief being four Corinthian pilasters for the pediment. However, although perhaps unremarkable from the outside, the interior was well adorned in his typical 'mature, baroque style'.

It was really the interiors where May excelled at Cassiobury - with the help of one of the finest wood carvers ever to work in England, Grinling Gibbons. John Evelyn wrote '...There are diverse faire and good roomes, and excellent carvings by Gibbons, especially the chimney piece of ye Library...'. Cassiobury was Gibbons first large scale work and the highlight was the superb staircase; adorned with pine-cone finials, and featuring various natural forms including swirling acanthus, oak leaves and acorns. Truly it was Gibbon's masterpiece as is the only known example of one of his staircases - despite the alternative attribution to Edmund Pearce by the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Cassiobury was not to remain untouched though by later fashions. With the arrival of the 5th Earl in 1799 he immediately engaged the famous architect James Wyatt (b.1746 - d.1813) to remodel the house. Wyatt was widely criticised by contemporary and later antiquarians for his destructive remodelling of cathedrals which involved removing anything later than a certain date. However, he was also widely admired for his confident handling of Gothic details which reached its zenith in his work for William Beckford and the vast Fonthill Abbey. The work was probably completed by 1804 when it's recorded that Prime Minister Pitt had visited Lord Essex there. Around the same time, Humphrey Repton was employed to landscape the park, introducing his distinctive style and features such as the lake and canal.

Although with Wyatt's reputation it might have seemed likely that he would have kept little, Wyatt actually only removed two front wings and then enclosed the courtyard. Inside, he retained 10 of May's reception rooms and Gibbon's woodcarvings. However, the exterior was regarded as unsuccessful - an unsatisfying neo-Gothic compromised by the proportions of the existing building.

It was certainly for the interiors which Country Life magazine featured the house in 1910. At that time Cassiobury was still a rural retreat described as;

'...set in great and delightful grounds and surrounded by a grandly timbered park. Therein is peace and quiet; the aloofness of the old-country home far from the haunts of men reigns there still, and Watford and its rows of villas and its busy streets is forgotten as soon as the lodge gates are passed'.

It was this relentless urban growth which eventually was to overrun the gate lodges. The 7th Earl died in 1916 after being hit by a taxi, and just six years later the estate was put up for sale by his widow and her son, the 8th Earl. The age of the large country house was facing its first period of crisis and the opportunity offered by selling the parkland for housing to cater for the expansion of Watford was very attractive.

The contents sale in June 1922 was a grand affair lasting over ten days - unsurprising really considering the huge range of items including four separate libraries to be sold. The Capels had long been collectors of art, with their galleries containing works by Turner, Lely, Landseer, Wilkie, and much furniture, particularly French. Cassiobury House with 485-acres was also offered but didn't sell until August when a group of local businessmen bought it for the development potential. The house was then stripped, with the Gibbons carvings being split between many museums and private collectors, and the remaining materials sold for re-use - some even making their way to America where at least one house was built mainly of the bricks. The house was then demolished in 1927 with Watford's suburbs expanding until today the site of the house is a residential estate with no sign of its former glory or grand associations.