Costessey Hall

Norfolk

| Location | Costessey | ||

| Year demolished | c.1918-20 | ||

| Reason | Damage from requisition during World War I | ||

| See all images: | Gallery | ||

| << Back to the main list |

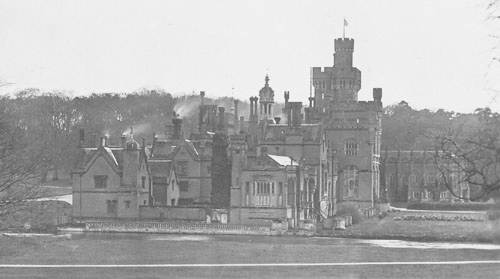

Costessey Hall presented a dramatic and romantic silhouette of turrets, chimneys, and crenellations - more reminiscent of a fantastical castle than a traditional country house. Sadly, this vision was to fall as another victim of the extensive damage which wartime requisition often visited upon a house.

The origins of the estate can be traced to the immediate post-Conquest period. Costessey Manor was granted by William the Conqueror following the Norman victory at Hastings in 1066, although the details of this early tenure remain somewhat opaque. By the mid-16th century, the manor had come into the possession of Sir Henry Jernegan (later Jerningham), who was rewarded by Queen Mary I in 1555 for his loyalty in proclaiming her the rightful monarch in 1553. As a prominent Catholic, Jernegan was part of a tradition of recusant landowners who maintained their estates in spite of religious and political marginalisation.

The origins of the estate can be traced to the immediate post-Conquest period. Costessey Manor was granted by William the Conqueror following the Norman victory at Hastings in 1066, although the details of this early tenure remain somewhat opaque. By the mid-16th century, the manor had come into the possession of Sir Henry Jernegan (later Jerningham), who was rewarded by Queen Mary I in 1555 for his loyalty in proclaiming her the rightful monarch in 1553. As a prominent Catholic, Jernegan was part of a tradition of recusant landowners who maintained their estates in spite of religious and political marginalisation.

Sir Henry abandoned the original manor house, which stood on the north bank of the River Tud in Costessey Park, and selected a new site on the river's southern side for his residence. Here, he constructed a substantial Tudor H-plan house, notable for its red brick construction, mullioned windows, and tall chimneys. In addition to the house, he commissioned a private chapel - an architectural necessity for a Catholic family forbidden from participating in the services of the established Church of England.

The house remained largely unchanged for over two centuries, a testament to its robust Tudor fabric. In the early 19th century, however, the Jerningham family, who had by then inherited the revived title of Baron Stafford (1824), undertook an ambitious and transformative expansion of the estate. Between 1826 and 1836, Lord Stafford Jerningham employed John Chessell Buckler, a noted Gothic Revival architect, to incorporate the existing Tudor core into a vastly enlarged mansion. Buckler’s design was characterised by its romantic medievalism: a sprawling, asymmetrical plan; a multitude of ornate chimneys, gables, turrets and pinnacles; and a dominant central keep that served as a picturesque rather than functional element.

The death of the last Lord Stafford Jerningham in 1913 marked the end of both the baronetcy and the family's occupation of Costessey Hall, with the contents auctioned off. Costessey Hall then stood empty until the large house with extensive parkland was inevitably requisitioned by the War Office at the outbreak of the First World War.

Unfortunately, with no resident owner to keep an eye on the fabric of the building, the infantry, cavalry, and artillery regiments stationed and trained on the estate inflicted considerable wear on the building's fabric. By 1919, the building was in such a poor condition that demolition was deemed the only viable course of action. The demise of Costessey Hall should be understood in the wider context of the fundamental changes to the traditional landed order in post-war Britain. Like many estates, it was ill-prepared to withstand the dual pressures of wartime requisition and peacetime taxation. Without a resident aristocratic owner and facing an unfavourable economic climate, the Hall fell rapidly into decline, its grandeur no defence against obsolescence.

As in the case with many of these demolitions, parts of Costessey Hall were re-used with a four-hundred-year old carved stone fireplace and oak linenfold panelling being re-used in nearby Hethersett Hall. The valuable stained glass was sold for £17,000 - a sum equivalent to approximately £600,000 in today’s money.

Now only the belfry block remains, standing guard over the 18th fairway of the Costessey Park Golf Club.